Ureaplasma Infection: Symptoms, Testing, and Treatment

You’ve either just tested positive for ureaplasma, or you’re dealing with symptoms your doctor can’t explain—recurrent UTIs with negative cultures, unexplained pelvic pain, or fertility struggles that standard testing hasn’t solved.

What makes ureaplasma confusing? It lives in 40-80% of sexually active adults without causing problems, yet it can trigger real complications when bacterial overgrowth occurs. Most resources either dismiss it as completely harmless or treat it like an emergency. The truth? Neither extreme is right.

This guide answers the questions that actually matter: when does ureaplasma require treatment, how do you know if it’s causing your symptoms, and what does the research really show about fertility and pregnancy risks. You’ll learn why standard STI tests miss it, why doctors resist testing, and how to determine whether your situation calls for antibiotics or just monitoring.

What Is Ureaplasma and Should You Be Concerned?

Quick Answer: Ureaplasma is common bacteria found in the urogenital tract of 40-80% of sexually active adults. Most people carry it without symptoms or health problems. It can cause urethritis, fertility complications, and pregnancy issues when bacterial overgrowth occurs or in those with weakened immunity—but that’s the exception, not the rule.

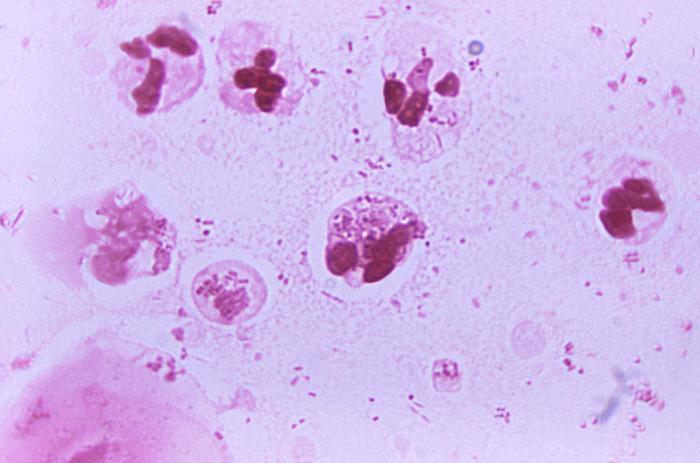

Ureaplasma belongs to the Mycoplasma family—bacteria so small they lack a cell wall. This makes them invisible under standard microscopes and resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin. These bacteria colonize the urinary and reproductive tracts, typically coexisting peacefully with other microbes in your body’s natural microbiome.

Here’s the key distinction: ureaplasma is a commensal organism, not an automatic infection. Think of it like yeast in your digestive system—present in most people, only problematic under certain conditions. When your immune system weakens, bacterial balance shifts, or colonization extends to areas it shouldn’t, that’s when ureaplasma transitions from harmless resident to potential troublemaker.

The Two Types of Ureaplasma: Why Species Matters

Not all ureaplasma is created equal. Two distinct species infect humans, and understanding the difference matters for treatment decisions—even though most testing won’t tell you which one you’re carrying.

Ureaplasma urealyticum: The More Problematic Species

U. urealyticum is the species consistently linked to urogenital symptoms and complications. Research shows it’s more likely to cause nongonococcal urethritis in men, contribute to pelvic inflammatory disease in women, and play a role in adverse pregnancy outcomes. When studies find associations between ureaplasma and fertility problems? U. urealyticum is typically the culprit.

This species appears less frequently than its cousin but punches above its weight in pathogenic potential. If you’re experiencing persistent pelvic pain, recurrent urinary issues, or unexplained fertility challenges, U. urealyticum is worth investigating.

Ureaplasma parvum: The Common but Quieter Type

U. parvum is detected in most clinical specimens—it’s far more prevalent but generally less pathogenic. Most people carrying U. parvum never develop symptoms or complications. Current research hasn’t consistently shown that U. parvum causes urogenital disease, though scientists continue studying its potential role in specific conditions.

Some fertility specialists treat both species in couples struggling to conceive. That said, the evidence supporting treatment for asymptomatic U. parvum colonization remains limited and controversial.

| Characteristic | U. urealyticum | U. parvum |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | Less common | More common |

| Pathogenic potential | Higher—linked to symptoms | Lower—usually harmless |

| Associated conditions | NGU, PID, infertility, pregnancy complications | Uncertain—research mixed |

| Treatment recommendation | Generally advised when symptomatic | Controversial unless symptoms present |

What This Means for Treatment Decisions

Since most tests can’t tell you which species you’re carrying, clinical context matters more than the test result itself. Symptoms, sexual health history, pregnancy plans, and whether other infections have been ruled out should guide treatment decisions—not a positive test alone.

How Ureaplasma Spreads: Sexual Contact and Vertical Transmission

Ureaplasma primarily spreads through intimate contact, but calling it a sexually transmitted infection oversimplifies its nature. Unlike chlamydia or gonorrhea—infections you acquire and should definitely treat—ureaplasma often colonizes people without causing disease.

Sexual Transmission: The Primary Route

Unprotected sexual contact transfers ureaplasma through genital-to-genital or oral-genital contact. Multiple sexual partners increases your likelihood of carrying it, as does early sexual debut.

Unlike typical STIs, many long-term monogamous couples both carry ureaplasma without either partner “giving it” to the other. It’s more like sharing mouth bacteria through kissing than transmitting a disease organism. However, when one partner develops symptomatic infection, treating both partners prevents reinfection.

Mother-to-Newborn Transmission

Pregnant women carrying ureaplasma can pass the bacteria to their babies during vaginal delivery. The bacteria colonizes the infant’s respiratory or urogenital tract as they pass through the birth canal. More than 20% of live-born infants may be colonized, with higher rates among preterm babies.

For full-term infants with developed immune systems, this colonization typically causes no problems and usually disappears within a few months without intervention. Premature infants face greater risk—ureaplasma can invade their bloodstream or cause respiratory infections like pneumonia, particularly in very low birth-weight babies whose immune systems aren’t ready to control bacterial populations.

What About Casual Contact?

You can’t catch ureaplasma from toilet seats, swimming pools, sharing towels, or other non-intimate contact. The bacteria requires direct mucous membrane contact to transfer and doesn’t survive long outside the human body. Nosocomial (hospital-acquired) transmission through contaminated medical instruments is theoretically possible but extremely rare.

Ureaplasma Symptoms in Men, Women, and Newborns

Here’s what makes ureaplasma tricky: roughly 70% of people carrying the bacteria experience no symptoms whatsoever. They’re asymptomatic carriers whose immune systems keep bacterial populations in check. For the remaining 30%, symptoms emerge when bacterial overgrowth occurs, immunity weakens, or ureaplasma colonizes areas beyond its typical territory.

This creates real diagnostic confusion. Many people discover ureaplasma only after exhausting other explanations for persistent symptoms. Your doctor might test for it as a last resort rather than a first consideration.

Female Symptoms: When Colonization Becomes Infection

Women with symptomatic ureaplasma infection most commonly report symptoms that overlap with bacterial vaginosis or urethritis. The bacterial overgrowth disrupts the vaginal microbiome’s delicate pH balance, creating an environment where harmful bacteria flourish alongside beneficial ones.

Common symptoms? Abnormal vaginal discharge that may appear yellow, green, or gray with an unusual odor. Burning during urination mimics a urinary tract infection, though standard urine cultures often return negative. Some women experience pelvic discomfort, pain during intercourse, or spotting between periods.

Chronic pelvic pain represents another presentation. Some women endure months of unexplained pelvic discomfort—a 9/10 burning sensation, pressure, or cramping—before ureaplasma testing reveals the culprit. This often follows after antibiotics for presumed UTIs provide only temporary relief.

Male Symptoms: Nonspecific Urethritis

Men carrying symptomatic ureaplasma typically develop nongonococcal urethritis (NGU)—inflammation of the urethra not caused by gonorrhea. U. urealyticum is a recognized cause of NGU, though chlamydia remains more common. Mycoplasma genitalium is another frequent cause.

Symptoms include clear or cloudy discharge from the penis, burning or pain during urination, and irritation or itchiness at the urethral opening. Unlike gonorrhea’s profuse, thick discharge, ureaplasma-related discharge tends to be minimal and may appear only in the morning.

The controversy: ureaplasma also colonizes healthy men without causing symptoms. Detecting it in someone with urethritis doesn’t automatically prove causation. This is why some urologists treat empirically with antibiotics covering multiple NGU causes rather than testing for specific organisms.

The Asymptomatic Carrier Reality

Most people carrying ureaplasma never know it. Their bacteria remain balanced with other microbiome inhabitants, causing no inflammation or symptoms. This is normal colonization, not infection.

Problems arise when routine testing identifies ureaplasma in someone without symptoms—during STI screening, pregnancy workups, or infertility evaluations. The positive result triggers unnecessary anxiety and pressure for treatment that provides no benefit.

Ureaplasma’s Impact on Fertility and Pregnancy Outcomes

This is where ureaplasma research gets messy. Studies show conflicting results about whether ureaplasma directly causes infertility or just associates with it. The truth? It likely depends on bacterial species, individual immune responses, and whether other reproductive tract infections coexist.

Male Fertility: Sperm Quality Effects

Research consistently shows associations between ureaplasma—particularly U. urealyticum—and reduced sperm quality. A 2023 study of 1,064 men aged 20-30 found that U. urealyticum presence correlated with lower sperm concentrations and decreased sperm motility (the ability to swim effectively toward an egg).

The mechanism appears to involve direct bacterial attachment to sperm cells. Ureaplasma can bind to sperm surfaces, potentially damaging cell membranes, distorting sperm shape, and impairing movement. Some researchers also suspect the bacteria triggers localized inflammation in reproductive tissues, indirectly affecting sperm production.

However—and this matters—many men with ureaplasma maintain normal fertility. Detection doesn’t equal infertility. Some fertility specialists treat couples struggling to conceive when ureaplasma is detected, while others remain skeptical without stronger evidence.

Female Fertility: The Tubal Factor Question

When ureaplasma ascends from the vagina into the upper reproductive tract—the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries—it can contribute to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Left untreated, PID causes scarring and adhesions that block fallopian tubes, preventing sperm from reaching eggs and creating tubal factor infertility.

A 2020 study found associations between ureaplasma and tubal factor infertility in women being evaluated for reproductive issues. But here’s the research complexity: a 2021 review found no association between U. urealyticum and female infertility, instead suggesting researchers should focus on U. parvum’s potential role.

What’s clear: ureaplasma probably isn’t the sole cause of most fertility issues. It may act as one contributing factor among many—age, hormonal imbalances, structural abnormalities, male factor issues—that together impact conception chances. Individual biology determines whether your ureaplasma colonization matters for fertility.

Pregnancy Complications: Real Risks for Preterm Birth

The strongest evidence for ureaplasma’s clinical significance involves pregnancy complications. When bacteria invade the amniotic sac and placental tissues, they trigger inflammatory responses that can lead to serious outcomes.

Documented associations include early membrane rupture (water breaking before labor begins), preterm birth (delivery before 37 weeks), chorioamnionitis (infection of the membranes surrounding the fetus), and pregnancy loss. A 2021 study examining bacterial causes of chorioamnionitis found ureaplasma was the most common organism detected.

The mechanism involves bacterial infiltration of placental tissues and amniotic fluid. Ureaplasma’s presence triggers immune cells to release inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins—compounds that soften the cervix and stimulate uterine contractions, potentially initiating labor prematurely.

Risks for Newborns: Premature Infants Most Vulnerable

Full-term babies exposed to ureaplasma during vaginal delivery typically clear the bacteria within months without complications. Their developed immune systems can control bacterial populations effectively.

Premature infants face different risks. Ureaplasma can invade their underdeveloped lungs, bloodstream, and cerebrospinal fluid, potentially causing pneumonia, sepsis, or meningitis. Chronic ureaplasma presence in premature lungs associates with bronchopulmonary dysplasia—a condition where lungs don’t develop properly, requiring prolonged oxygen support.

Very low birth-weight babies (under 1,500 grams) show the highest risk. Their immature immune systems can’t effectively clear bacteria, and invasive medical procedures like ventilation provide entry points for infection.

When to Test for Ureaplasma (and Why Doctors Often Resist)

Here’s where the ureaplasma story gets frustrating for patients: your doctor may resist testing for it, dismiss your positive result as insignificant, or refuse treatment despite your symptoms. Understanding the medical controversy? That helps you navigate these conversations more effectively.

The Commensal vs. Pathogen Debate

Medical training teaches that ureaplasma is typically commensal—part of the normal urogenital microbiome in sexually active adults. Because it’s so prevalent in healthy people, many clinicians view positive tests in asymptomatic patients as clinically meaningless.

This perspective has merit. We wouldn’t treat someone for Lactobacillus or E. coli just because testing detected these bacteria in appropriate body sites. The question is whether ureaplasma sometimes crosses the line from harmless resident to disease-causing pathogen.

The evidence suggests it does—under specific circumstances. U. urealyticum can cause urethritis, contributes to pregnancy complications, and may impact fertility. But detecting it doesn’t automatically mean it’s causing your problems. Context matters enormously.

When Testing Makes Clinical Sense

Several situations warrant ureaplasma testing:

Recurrent UTI symptoms with negative cultures: Standard urine cultures miss ureaplasma. Persistent UTI symptoms with repeatedly negative tests suggest specialized testing for ureaplasma or mycoplasma genitalium.

Unexplained infertility: After standard fertility workups identify no causes, testing both partners for ureaplasma urealyticum may reveal treatable factors affecting male sperm quality or female tubal function.

Pregnancy complications: Women with history of preterm birth, recurrent pregnancy loss, or signs of intrauterine infection may benefit from testing.

Persistent pelvic pain: When endometriosis has been treated, anatomical issues ruled out, and other infections tested, ureaplasma parvum or urealyticum remains a potential explanation.

Nongonococcal urethritis: Men with urethritis testing negative for gonorrhea and chlamydia should be evaluated for ureaplasma infection and mycoplasma genitalium.

Why Standard STI Tests Miss Ureaplasma

Most STI panels test for gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, syphilis, and sometimes herpes or trichomoniasis. Ureaplasma typically isn’t included unless specifically requested. There are practical reasons for this exclusion.

Standard urine cultures—the go-to test for urinary symptoms—won’t detect ureaplasma. These bacteria lack cell walls and require specialized growth media. They form tiny colonies that standard bacterial cultures miss entirely.

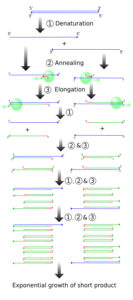

Detection requires either specialized culture methods (growing bacteria on specific media like A8 agar) or PCR testing that identifies bacterial DNA. PCR has become the preferred method—it’s faster (results in days versus weeks), more sensitive, and doesn’t require viable bacteria.

The Self-Advocacy Gap

Many patients discover ureaplasma only through their own research after standard testing fails to explain persistent symptoms. They must specifically request testing, often encountering resistance from providers who consider it unnecessary.

This creates a real diagnostic gap. Women experiencing chronic UTI symptoms with negative cultures, couples facing unexplained fertility issues, or people with persistent pelvic pain might harbor ureaplasma infections that remain undetected simply because no one thought to look.

If you suspect ureaplasma might explain your symptoms, approach your healthcare provider with specific reasons: “I’ve had three negative urine cultures despite UTI symptoms” or “We’ve been trying to conceive for 18 months without identifying any causes.” Explaining why you’re requesting testing—beyond just wanting the test—helps providers understand your clinical reasoning.

Samples for testing include vaginal swabs (women), urethral swabs or first-void urine (men), or amniotic fluid/placental tissue (pregnancy complications). Labs like Labcorp and Quest Diagnostics offer ureaplasma PCR testing, though you’ll need a provider order.

Treating Ureaplasma: Antibiotics, Partner Treatment, and Reinfection Prevention

If testing confirms ureaplasma and your clinical situation warrants treatment—you’re symptomatic, facing fertility challenges, or pregnant with complications—antibiotics remain the only effective intervention. But here’s the catch: not just any antibiotics will work.

Why Common Antibiotics Fail

Remember that ureaplasma lacks a cell wall? This seemingly minor detail has major treatment implications. Beta-lactam antibiotics—the penicillin and cephalosporin families that treat most bacterial infections—work by disrupting bacterial cell wall synthesis. No cell wall? These drugs are completely ineffective against ureaplasma.

This explains why some people get temporary symptom relief with amoxicillin or cephalexin for presumed UTIs, only to have symptoms return. They’re not treating the actual infection.

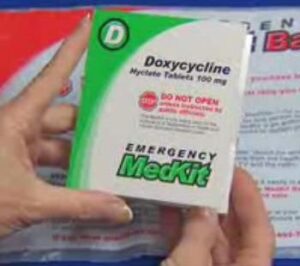

First-Line Treatment: Doxycycline

Doxycycline is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for ureaplasma infection. Standard dosing is 100mg twice daily for 14 days. While some providers prescribe 7-day courses, 14 days provides better eradication rates, particularly for U. urealyticum.

Tetracyclines work by blocking bacterial protein synthesis. Important: take them separate from dairy products, calcium supplements, or antacids. They’re contraindicated during pregnancy and for children under 8 years old.

Macrolide Alternatives

Azithromycin offers an alternative approach, often used in combination with doxycycline or when tetracyclines are contraindicated. The typical protocol involves either a single 1-gram dose or 500mg daily for 3 days following the doxycycline course.

Macrolides also inhibit protein synthesis but through a different mechanism than tetracyclines. Azithromycin has the advantage of pregnancy safety (Category B), making it suitable for pregnant women when treatment is necessary.

Some practitioners use clarithromycin instead—it demonstrates good activity against ureaplasma in laboratory studies. However, growing macrolide resistance is a concern, with resistance rates varying by geographic region and antibiotic exposure patterns.

Fluoroquinolones: Third-Line Options

Levofloxacin or moxifloxacin serve as third-line options when first-line antibiotics fail or can’t be used. These fluoroquinolones inhibit bacterial DNA replication by blocking DNA gyrase enzymes.

However, fluoroquinolones carry black box warnings for tendon rupture, nerve damage, and other serious side effects. They’re typically reserved for cases where other options have failed or resistance has been documented.

The Partner Treatment Imperative

Here’s a critical point many people miss: if you’re being treated for symptomatic ureaplasma infection, your sexual partner needs simultaneous treatment—even without symptoms. Otherwise? You’re playing ping-pong with the bacteria, passing it back and forth through sexual contact.

Both partners should complete full antibiotic courses and abstain from sexual contact until treatment is finished. This prevents reinfection and breaks the transmission cycle.

The exception: asymptomatic partners of people receiving treatment for fertility purposes (where no active infection exists) remain controversial. Some fertility specialists treat both partners empirically, while others treat only the symptomatic individual.

Test-of-Cure: Confirming Eradication

Wait at least 4 weeks after completing antibiotics before retesting. Testing too early may detect dead bacterial DNA fragments, yielding false-positive results. You want to confirm that viable, replicating bacteria have been eliminated.

Some providers recommend testing both urine and vaginal swab samples to ensure comprehensive eradication, particularly if symptoms persist or fertility remains a concern.

Debunking Common Ureaplasma Myths

The internet is full of oversimplified, fear-based, or outright incorrect information about ureaplasma. Let’s separate medical evidence from misconceptions using research to challenge claims you’ll find on forums and misinformed healthcare blogs.

Myth #1: “Ureaplasma Is Always Harmless”

The Reality: While ureaplasma colonizes most sexually active adults without problems, U. urealyticum demonstrably causes nongonococcal urethritis, associates with pregnancy complications, and correlates with reduced sperm quality. Individual biology? That’s what determines whether colonization remains benign or becomes problematic.

Myth #2: “Standard STI Tests Detect Ureaplasma”

The Reality: Routine STI panels test for gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis—not ureaplasma. Standard urine cultures miss these bacteria entirely because they lack cell walls and require specialized PCR testing. You can test negative for “everything” while harboring symptomatic ureaplasma infection. It happens more often than you’d think.

Myth #3: “You Can Treat Ureaplasma Naturally”

The Reality: Active ureaplasma infection requires antibiotics. Period. Herbal supplements, probiotics, or dietary changes won’t eliminate bacterial overgrowth causing urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or pregnancy complications. Supporting your microbiome during treatment? That makes sense. But probiotics don’t replace antibiotics for active infection.

Myth #4: “Everyone With Ureaplasma Needs Treatment”

The Reality: Detecting ureaplasma in someone without symptoms, pregnancy complications, or fertility issues typically doesn’t warrant treatment. You’re colonized, not infected. Treatment eliminates bacteria that may be harmlessly coexisting with your microbiome, potentially disrupting bacterial balance without providing health benefits.

Myth #5: “Ureaplasma Always Causes Infertility”

The Reality: Research shows associations between U. urealyticum and fertility challenges, but many people with ureaplasma conceive without difficulty. It may contribute as one factor among many—age, hormones, anatomy, other infections—rarely as the sole cause. Some couples report successful conception after treatment, but controlled studies are lacking.

The Evidence-Based Middle Ground

Ureaplasma represents a commensal organism that sometimes causes disease under specific circumstances. Clinical context matters enormously—your symptoms, sexual health history, pregnancy status, and fertility concerns determine whether testing and treatment make sense. Evidence-based medicine means treating people, not test results.

Preventing Ureaplasma and Supporting Urogenital Health

Since ureaplasma primarily spreads through sexual contact, prevention strategies overlap with general sexual health practices. But unlike preventing definite pathogens like gonorrhea, ureaplasma prevention involves a more nuanced approach. You’re not trying to avoid all exposure to ubiquitous bacteria—you’re maintaining conditions that keep colonization from becoming problematic.

Barrier Protection: Reducing Transmission Risk

Condoms and dental dams reduce ureaplasma transmission during sexual activity. They’re not perfect—ureaplasma can colonize areas barriers don’t cover—but they significantly decrease exposure risk.

For people with recurrent ureaplasma infections or those whose partners carry it, consistent barrier use during treatment and for several weeks afterward prevents immediate reinfection. After both partners complete treatment and test negative? You can reassess whether continued barrier use makes sense for your situation.

Maintaining Vaginal pH Balance

Ureaplasma thrives when vaginal pH rises above the healthy acidic range (3.8-4.5). Supporting your vaginal microbiome’s natural acidity helps control bacterial populations.

Skip douches, scented products, and unnecessary “feminine hygiene” items—these disrupt pH balance and eliminate beneficial Lactobacillus bacteria. Wash only the external vulva with plain water. Some evidence supports lactic acid-based vaginal gels for maintaining healthy pH, particularly after antibiotic courses.

Smart Antibiotic Use and Immune Support

Every antibiotic course disrupts your microbiome, potentially allowing ureaplasma overgrowth. Use antibiotics when truly needed—bacterial pneumonia, serious UTIs—but question whether they’re necessary for viral infections or minor issues that would resolve naturally.

Your immune system keeps ureaplasma populations controlled. Support immune function through adequate sleep, stress management, and balanced nutrition. People with immunosuppression—from HIV, organ transplantation, or chemotherapy—face higher risks and should discuss screening with their healthcare team.

The Bottom Line

Most people carrying ureaplasma coexist peacefully with these bacteria without problems. The goal isn’t eliminating all ureaplasma—that’s neither possible nor necessary. Focus on recognizing when colonization transitions to infection and maintaining conditions that keep bacterial populations in check. If you’ve been treated successfully, recolonization doesn’t automatically mean reinfection or warrant retreatment without symptoms.

Understanding Ureaplasma: Moving Forward With Clarity

Ureaplasma isn’t the silent epidemic some sources claim, nor is it universally harmless as dismissive providers might suggest. The reality sits in the nuanced space between—where bacterial species, symptom presence, immune function, and individual biology determine whether colonization matters for your health.

What you need to remember: positive tests in asymptomatic people rarely warrant treatment, while persistent symptoms with negative standard testing justify ureaplasma evaluation. U. urealyticum poses greater concern than U. parvum (though most testing won’t differentiate between them). Partner treatment prevents reinfection when active infection exists. And antibiotics work when truly needed—but preserving your microbiome means treating infections, not colonization.

If you’re experiencing unexplained urogenital symptoms, facing fertility challenges, or dealing with pregnancy complications, you now understand when ureaplasma testing makes clinical sense. You also have the language to discuss it with your healthcare provider. Trust your symptoms. Question test results that don’t match your clinical picture. And remember that evidence-based medicine treats people, not laboratory numbers.

References

- Waites KB, Xiao L, Paralanov V, Viscardi RM, Glass JI. Molecular methods for the detection of Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma infections in humans: a paper from the 2011 William Beaumont Hospital Symposium on molecular pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14(5):437-450. View source

- Xiao L, Glass JI, Paralanov V, et al. Detection and characterization of human Ureaplasma species and serovars by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(8):2715-2723. View source

- Huang C, Zhu HL, Xu KR, Wang SY, Fan LQ, Zhu WB. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma infection and male infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2015;3(5):809-816. View source

- Zhao F, Zhou M, Wang Y, Zhong W, Li W. The relationship between Ureaplasma urealyticum infection and sperm quality in infertile males. BMC Urol. 2023;23(1):41. View source

- Sweeney EL, Dando SJ, Kallapur SG, Knox CL. The Human Ureaplasma Species as Causative Agents of Chorioamnionitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(1):349-379. View source

- Viscardi RM. Ureaplasma species: role in neonatal morbidities and outcomes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99(1):F87-F92. View source

- Gdoura R, Kchaou W, Chaari C, et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum, Ureaplasma parvum, Mycoplasma hominis and Mycoplasma genitalium infections and semen quality of infertile men. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:129. View source

- Horner P, Donders G, Cusini M, Gomberg M, Jensen JS, Unemo M. Should we be testing for urogenital Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum in men and women? – a position statement from the European STI Guidelines Editorial Board. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(11):1845-1851. View source

- Redelinghuys MJ, Ehlers MM, Dreyer AW, Lombaard H, Kock MM. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Ureaplasma species and Mycoplasma hominis in pregnant women. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:171. View source

- Pararas MV, Skevaki CL, Kafetzis DA. Preterm birth due to maternal infection: Causative pathogens and modes of prevention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25(9):562-569. View source

Medical Disclaimer

Important: The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Ureaplasma diagnosis and treatment decisions should be made in consultation with qualified healthcare providers who can evaluate your individual circumstances, symptoms, and medical history. Do not start, stop, or modify any medical treatment based solely on information from this article. If you’re experiencing symptoms of urogenital infection, pregnancy complications, or fertility concerns, seek evaluation from appropriate medical professionals. Testing and treatment protocols may vary based on your location, healthcare system, and individual clinical presentation.