Yes! Exercise lowers blood pressure by 5-8 mmHg on average. Discover which types work best, how much you need, and proven workout plans to reduce hypertension naturally.”>

Does Exercise Lower Blood Pressure? The Science-Backed Answer

If you’ve been diagnosed with high blood pressure, your doctor has probably recommended exercise. But you might wonder: does exercise really lower blood pressure, or is it just something doctors say to avoid prescribing more medication?

The answer is backed by decades of research: exercise is one of the most powerful non-drug treatments for high blood pressure. Studies show that regular physical activity can reduce blood pressure as effectively as some medications.

But here’s what makes exercise even more compelling. It doesn’t just lower your numbers temporarily. Regular workouts create lasting changes in your cardiovascular system that help control blood pressure for the long term.

So let’s explore exactly how exercise affects blood pressure, which types work best, and how much you need to see results.

The Scientific Evidence: Does Exercise Really Lower Blood Pressure?

Research leaves no doubt that exercise lowers blood pressure. Multiple large-scale analyses examining hundreds of studies consistently show significant blood pressure reductions from regular physical activity.

A comprehensive meta-analysis published in the American Heart Association journal Hypertension found that increasing physical activity lowers systolic and diastolic blood pressure by an average of 3-4 mmHg. That might sound small, but these reductions significantly decrease cardiovascular risk.

Another major review analyzing 47 clinical trials with over 2,500 participants found that aerobic exercise reduced blood pressure by 6 mmHg systolic and 5 mmHg diastolic in people with hypertension. In those with normal blood pressure, reductions were smaller but still significant at 2 mmHg systolic and 1 mmHg diastolic.

How Much Do These Reductions Matter?

You might think a 5-8 mmHg reduction sounds modest. But cardiovascular risk is extremely sensitive to even small blood pressure changes. Research shows that reducing systolic pressure by just 2 mmHg decreases stroke mortality by 6%, coronary heart disease deaths by 4%, and all-cause mortality by 3%.

So a 6 mmHg reduction from exercise could potentially reduce your stroke risk by about 18% and heart disease risk by 12%. Those are meaningful benefits for something as simple as regular physical activity.

How Exercise Lowers Blood Pressure

Understanding the mechanisms behind exercise’s blood pressure benefits helps explain why it works so well. Exercise affects your cardiovascular system through multiple pathways, creating both immediate and long-term changes.

These mechanisms work together synergistically. You don’t get just one benefit from exercise – you get all of them simultaneously, which explains why the blood pressure-lowering effects are so robust.

Post-Exercise Hypotension: The 24-Hour Effect

One fascinating aspect of exercise and blood pressure is post-exercise hypotension. This refers to the sustained blood pressure reduction that occurs after a single workout session.

Research shows that your blood pressure stays lower for up to 24 hours after exercising. This means that if you work out most days of the week, you maintain continuously reduced blood pressure rather than just experiencing temporary dips.

The magnitude of post-exercise hypotension varies by individual, but reductions of 5-10 mmHg for several hours are common. This effect is particularly pronounced in people with hypertension compared to those with normal blood pressure.

Which Type of Exercise Works Best for Blood Pressure?

Not all exercise affects blood pressure equally. Recent research has clarified which types provide the greatest benefits, and the answers might surprise you.

A groundbreaking 2023 analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine examined nearly 300 randomized trials involving over 15,000 people. The researchers compared five different exercise types to determine which lowered blood pressure most effectively.

| Exercise Type | Average BP Reduction | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Isometric Exercise | Highest reductions observed | Wall sits, planks, hand grips – static muscle contractions |

| Aerobic Exercise | 5-7 mmHg reduction | Walking, cycling, swimming – most studied and accessible |

| High-Intensity Interval Training | 4-5 mmHg reduction | Alternating intense bursts with recovery – time-efficient |

| Dynamic Resistance Training | 4-5 mmHg reduction | Weight lifting, strength training – builds muscle |

| Combined Training | 6-8 mmHg reduction | Aerobic plus resistance – comprehensive benefits |

Interestingly, the study found that isometric exercise (holding static positions like wall sits or planks) produced the largest blood pressure reductions. However, aerobic exercise remains the most recommended because it’s been studied most extensively and is easiest for most people to maintain long-term.

Aerobic Exercise: The Gold Standard

Aerobic exercise – activities that increase your heart rate and breathing for sustained periods – has the most robust evidence for blood pressure reduction. The American Heart Association recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly for blood pressure control.

Moderate-intensity aerobic activities include brisk walking, leisurely cycling, swimming, dancing, and gardening. You should be able to talk but not sing during these activities. That’s often called the “conversational pace” test.

The good news is that you don’t need to run marathons or spend hours at the gym. Moderate activities performed regularly provide substantial benefits. Even 30 minutes of brisk walking five days per week can significantly lower your blood pressure.

Resistance Training: Strength for Your Heart

For years, doctors worried that lifting weights might spike blood pressure dangerously. However, research now shows that dynamic resistance training (lifting and lowering weights) safely lowers blood pressure when performed correctly.

Dynamic resistance exercise involves moving weights through a full range of motion, like bicep curls or squats. This differs from isometric exercise where you hold a static position.

Studies show that resistance training reduces blood pressure by about 4-5 mmHg. Plus, building muscle mass increases your resting metabolic rate, helps with weight management, and improves insulin sensitivity – all of which contribute to better blood pressure control.

Isometric Exercise: The Surprising Winner

Recent research has brought isometric exercise into the spotlight for blood pressure management. Mayo Clinic Health System reports that isometric exercises can be particularly effective for lowering blood pressure.

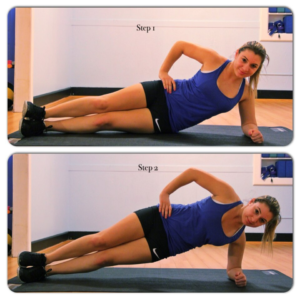

Isometric exercises involve contracting specific muscles without moving the joints. Think wall sits, planks, handgrip exercises, or holding a squat position. These exercises create sustained muscle tension that triggers beneficial cardiovascular adaptations.

Isometric Exercise Examples

- Wall sits (hold squat position against wall)

- Planks (hold push-up position on forearms)

- Handgrip exercises (squeeze and hold)

- Leg raises (hold leg extended)

- Dead hangs (hang from pull-up bar)

Why Isometric Works Well

- Improves blood vessel function

- Requires minimal equipment or space

- Suitable for people with joint issues

- Can be done almost anywhere

- Low impact on joints

However, isometric exercise should complement rather than replace aerobic activity. The overall cardiovascular benefits of aerobic exercise extend beyond blood pressure to include improved cholesterol, better glucose control, and enhanced cardiorespiratory fitness.

How Much Exercise Do You Need?

You probably want to know exactly how much exercise it takes to lower your blood pressure. The answer depends on your current fitness level, blood pressure readings, and other health factors.

Current guidelines from major health organizations provide clear recommendations. But here’s the encouraging part: you don’t need to exercise for hours daily to see benefits. Even small amounts of physical activity produce measurable improvements.

Minimum Effective Dose

The American Heart Association recommends these minimum activity levels for cardiovascular health and blood pressure control:

Standard Exercise Recommendations:

- Aerobic Activity: 150 minutes of moderate-intensity OR 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity weekly

- Muscle Strengthening: Two or more sessions per week targeting major muscle groups

- Frequency: Spread aerobic activity throughout the week (at least 3-5 days)

- Duration: Sessions can be as short as 10 minutes and still provide benefits

- Intensity: Moderate means you can talk but not sing; vigorous means you can only say a few words

For people specifically trying to lower blood pressure, some research suggests benefits from even more activity. Studies show dose-response relationships, meaning more exercise generally produces greater blood pressure reductions up to a point.

The Dose-Response Relationship

Interesting research has examined exactly how much exercise produces optimal blood pressure benefits. One study divided people with hypertension into groups exercising 30-60, 61-90, 91-120, or more than 120 minutes weekly.

The results showed progressively greater blood pressure reductions with more exercise time, but the biggest jump occurred when people went from sedentary to exercising 60-90 minutes weekly. Beyond that, benefits continued but with diminishing returns.

This means you’ll see significant benefits from meeting the standard 150-minute weekly recommendation. Exercising more than that provides additional benefits but perhaps not proportionally greater ones.

Every Bit Counts

Don’t let the 150-minute weekly goal intimidate you if you’re currently inactive. Research clearly shows that some physical activity is better than none, and benefits begin with even small amounts.

Starting with just 5-10 minutes of daily walking can produce measurable improvements. Then you can gradually increase duration and intensity as your fitness improves. This progressive approach is safer and more sustainable than trying to do too much too quickly.

Creating Your Blood Pressure-Lowering Exercise Plan

Knowing that exercise lowers blood pressure is one thing. Actually implementing a sustainable exercise routine is another. Let’s create a practical plan you can start today.

The best exercise program is one you’ll actually maintain. Don’t choose activities you hate just because you think they’re “supposed to” be best for blood pressure. Find movements you enjoy, or at least don’t mind, and build from there.

Getting Started Safely

Before starting any new exercise program, especially if you have high blood pressure or other health conditions, consult your healthcare provider. This is particularly important if your blood pressure is very high (over 180/110), you have heart disease, or you’ve been sedentary for a long time.

Once cleared to exercise, start gradually. If you’re currently inactive, begin with 10-15 minute sessions of low-intensity activity like casual walking. Don’t worry about hitting the 150-minute weekly goal immediately. Build up slowly over weeks or months.

Sample Weekly Exercise Plans

Here are three progressive exercise plans designed for different fitness levels. Choose the one that matches where you are now, not where you think you should be.

| Fitness Level | Weekly Plan | Total Weekly Minutes |

|---|---|---|

| Beginner (Currently Inactive) | • 10-15 min walks, 5 days/week • Light stretching, 2 days/week | 50-75 minutes |

| Intermediate (Some Activity) | • 25-30 min brisk walks, 5 days/week • Strength training, 2 days/week | 150-180 minutes |

| Advanced (Regular Exerciser) | • 40-45 min cardio, 4-5 days/week • Strength training, 2-3 days/week • Isometric exercises, 2 days/week | 200-250 minutes |

Remember that these are guidelines, not rigid requirements. Adjust based on your schedule, preferences, and how your body responds. The key is consistency over perfection.

Making Exercise a Habit

The blood pressure benefits of exercise only last as long as you keep exercising. Once you stop, your pressure gradually returns to previous levels over weeks to months. So the real challenge is making physical activity a permanent part of your lifestyle.

Strategies for Long-Term Success:

- Schedule it: Put exercise appointments in your calendar like any other commitment

- Start small: Build confidence with achievable goals before advancing

- Find a buddy: Exercise partners provide accountability and make workouts more enjoyable

- Track progress: Monitor your blood pressure readings to see the benefits motivate you

- Vary activities: Prevent boredom by trying different exercises

- Prepare for obstacles: Have backup plans for bad weather, busy days, or travel

- Celebrate milestones: Acknowledge improvements in fitness and blood pressure

Also consider joining group classes, walking clubs, or recreational sports leagues. Social connections around exercise improve adherence and make physical activity feel less like a chore.

Exercise for Resistant Hypertension

Some people have what’s called resistant hypertension – blood pressure that remains high despite taking three or more medications. You might wonder whether exercise can still help in these difficult cases.

The answer is yes. Research published in Hypertension found that regular aerobic exercise significantly lowered blood pressure even in people with resistant hypertension.

In one study, people with treatment-resistant high blood pressure who exercised for 40 minutes three times weekly reduced their systolic pressure by 7.1 mmHg and diastolic by 5.1 mmHg. These reductions occurred while participants continued all their regular medications.

This finding is crucial because it means exercise works through different mechanisms than blood pressure medications. Even when medications aren’t fully effective, exercise provides complementary benefits that can help achieve better control.

Precautions and Special Considerations

While exercise is generally safe and beneficial for most people with high blood pressure, certain situations require extra caution or modified approaches.

When Exercise Might Raise Blood Pressure

During exercise, blood pressure normally rises temporarily. Your systolic pressure might reach 160-190 mmHg during vigorous activity even if you have normal resting blood pressure. This is a normal physiological response.

However, some people experience exaggerated blood pressure spikes during exercise (systolic over 200-210 mmHg in men or 190 mmHg in women). This condition, called exercise-induced hypertension, may predict future permanent high blood pressure and requires medical evaluation.

Also be aware that blood pressure can drop suddenly after exercise, especially in hot weather or if you’re dehydrated. This post-exercise hypotension usually isn’t dangerous, but it can cause dizziness. Cool down gradually and stay hydrated to minimize this risk.

Medication Timing and Exercise

If you take blood pressure medications, consider timing your exercise when your medication is working optimally. This helps prevent excessively high readings during activity while also avoiding dangerous drops if your pressure goes too low.

Some blood pressure medications, particularly beta-blockers, can reduce your heart rate response to exercise. This is normal and doesn’t mean exercise isn’t working. You may need to use perceived exertion (how hard the activity feels) rather than target heart rate to gauge intensity.

Never adjust or stop your blood pressure medications without consulting your doctor, even if exercise is effectively lowering your readings. Your healthcare provider can help you safely reduce medications if appropriate.

Combining Exercise With Other Blood Pressure Strategies

Exercise works best as part of a comprehensive approach to blood pressure management. Combining physical activity with other lifestyle modifications and appropriate medications produces the greatest benefits.

For complete guidance on managing blood pressure through diet, supplements, medications, and lifestyle changes, visit our detailed guide on effective high blood pressure management strategies.

The Synergistic Effect

Lifestyle changes work synergistically, meaning their combined effect exceeds the sum of individual interventions. For example, exercise plus the DASH diet produces greater blood pressure reductions than either approach alone.

| Intervention | Typical BP Reduction | Combined Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise alone | 5-8 mmHg | Combined interventions can reduce blood pressure by 15-20 mmHg or more |

| DASH diet | 8-14 mmHg | |

| Sodium reduction | 4-8 mmHg | |

| Weight loss (10 lbs) | 5-10 mmHg | |

| Alcohol reduction | 2-4 mmHg |

This synergistic effect means you don’t necessarily need to be perfect in every area. Making moderate improvements across multiple lifestyle factors often produces better results than extreme changes in just one area.

Monitoring Your Progress

Tracking both your exercise consistency and blood pressure changes helps you see the connection between your efforts and results. This feedback loop provides powerful motivation to maintain your exercise routine.

Consider keeping a simple log where you record your daily or weekly exercise along with periodic blood pressure readings. You’ll likely notice that in weeks when you exercise consistently, your blood pressure readings trend lower.

What to Track:

Validated upper-arm cuff devices are recommended for accurate home readings. Photo: Donald Trung Quoc Don. License: CC BY-SA 4.0 Exercise type, duration, and intensity for each session

- Blood pressure readings (aim for at least weekly)

- Resting heart rate (decreases indicate improved fitness)

- Body weight (if weight loss is a goal)

- How you feel during and after exercise

- Any symptoms or concerns

Most people begin seeing blood pressure improvements within 4-8 weeks of starting regular exercise. However, cardiovascular fitness improvements often become noticeable even sooner – you’ll find activities that once felt difficult becoming easier.

When to Expect Results

One common question is: how quickly does exercise lower blood pressure? The timeline varies by individual, but research provides general expectations.

Acute effects occur immediately. Blood pressure drops within minutes after finishing a workout and stays reduced for up to 24 hours. So you experience some benefit from your very first exercise session.

Chronic adaptations take longer. Sustained blood pressure reductions from regular exercise training typically become evident after 4-12 weeks. The exact timing depends on your starting fitness level, exercise intensity and frequency, and other factors.

Don’t get discouraged if you don’t see dramatic changes in the first few weeks. Keep exercising consistently, and trust that beneficial cardiovascular adaptations are occurring even before your blood pressure readings reflect them.

Take the First Step Today

The evidence is overwhelming: exercise definitely lowers blood pressure. Regular physical activity reduces readings by 5-8 mmHg on average, with some people experiencing even greater benefits. These reductions translate to significantly reduced risks of heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular death.

The beauty of exercise as a blood pressure treatment is that it requires no prescription, causes no harmful side effects, and provides numerous additional health benefits beyond blood pressure control. You improve your mood, sleep better, maintain a healthy weight, reduce stress, and enhance overall quality of life.

You don’t need expensive equipment or gym memberships to get started. A pair of comfortable shoes and 10-15 minutes daily is enough to begin seeing benefits. Then gradually build from there as your fitness improves.

Remember that exercise works best when maintained long-term. The goal isn’t to exercise intensely for a few weeks then stop. Instead, find activities you enjoy enough to continue indefinitely. Make physical activity a permanent part of your lifestyle, and your cardiovascular system will thank you for decades to come.

So whether you’re trying to avoid blood pressure medications, reduce your current dosage, or simply optimize your cardiovascular health, exercise provides a powerful, proven, and accessible solution. The question isn’t whether exercise lowers blood pressure – research has definitively answered yes. The real question is: when will you start?

References

- Mayo Clinic. (2024). Exercise: A drug-free approach to lowering high blood pressure. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- American Heart Association. Getting Active to Control High Blood Pressure. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- American Heart Association. (2021). Doctors should ‘prescribe’ exercise for adults with slightly high blood pressure, cholesterol. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2023). How does exercise affect blood pressure? Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2021). Aerobic exercise helps hard-to-treat high blood pressure. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- Mayo Clinic Health System. (2024). Isometric exercise and blood pressure. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2024). Exercise and the Heart. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Acute and Chronic Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise on Ambulatory Blood Pressure. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- PubMed. (2002). Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

- American Heart Association Journal Hypertension. Physical Activity as a Critical Component of First-Line Treatment for Elevated Blood Pressure or Cholesterol. Retrieved September 30, 2025.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Exercise programs for people with high blood pressure require professional medical supervision and evaluation. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider before starting any new exercise program, especially if you have hypertension, heart disease, or other health conditions. Individual exercise responses and blood pressure changes may vary. This information should not replace professional medical guidance, regular blood pressure monitoring, or prescribed medications.